The past may be rose tinted but let’s be honest, the present is pretty shit.

We’re led to believe that progress is inextricably tethered to the inevitable march of time and that slowly but surely we are becoming healthier, better informed and more enlightened. I’m sorry, but that’s bullshit.

I’m fully aware of the more positive thesis or the ‘New Optimist’ movement, as it’s become known. In fact, I’m a big fan of Steven Pinker and Matt Ridley. I get that we are living longer, more fulfilled lives, that we’re better connected and less likely to die at the hands of another man etc but there are some nasty looking, gaping holes in this argument that are worth poking at right now.

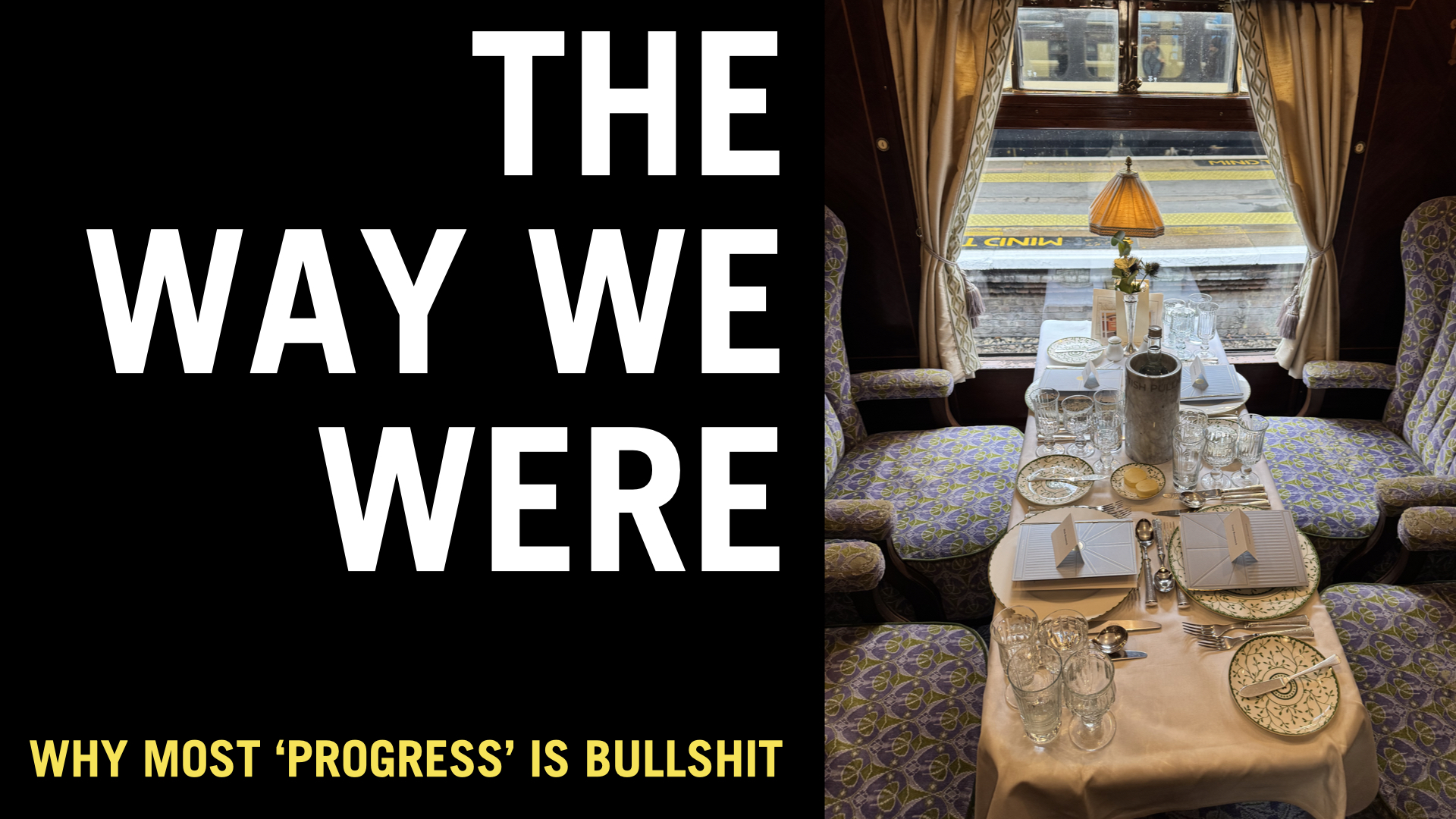

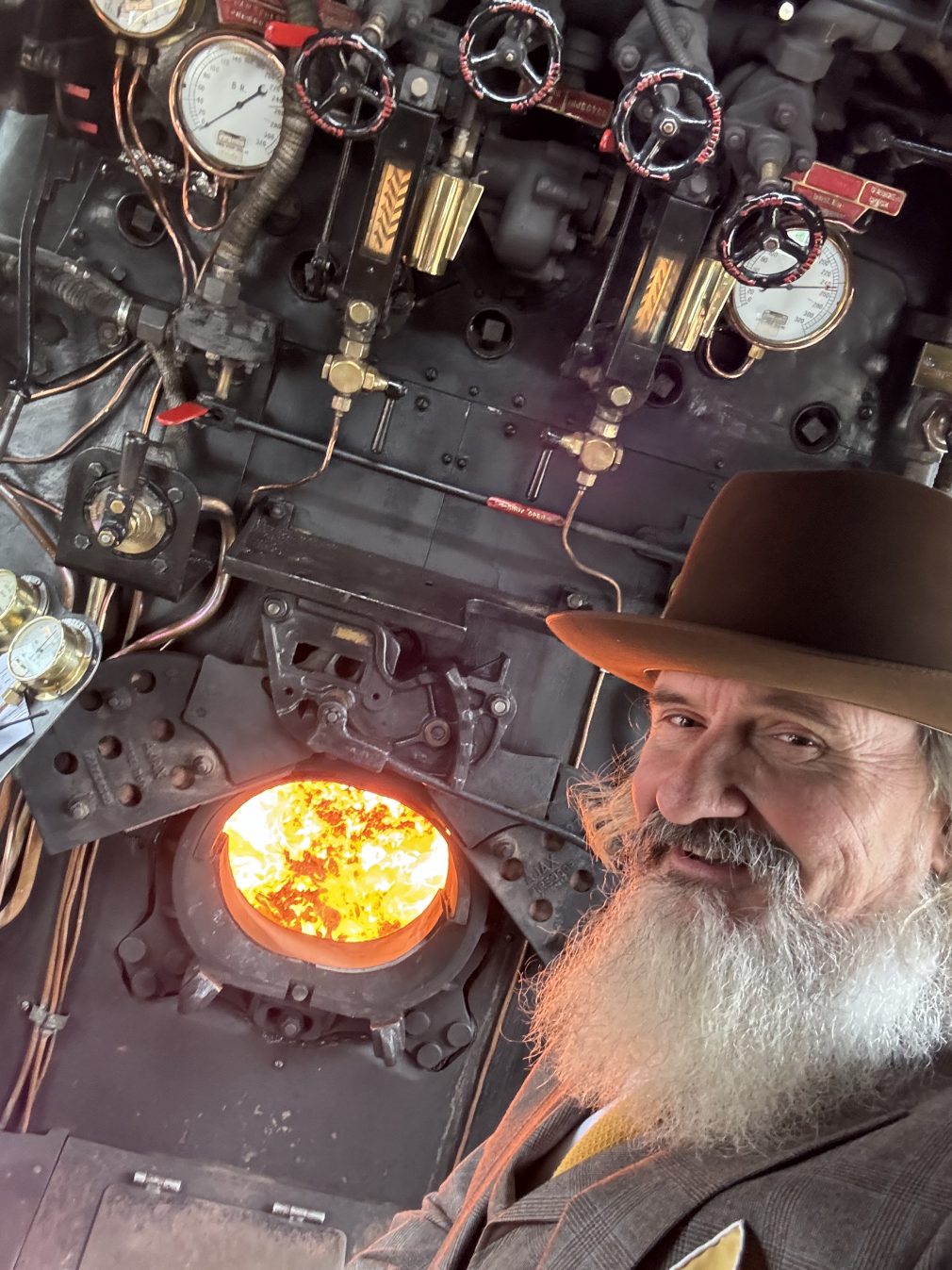

I had the pleasure recently of an eye-wateringly expensive jaunt in a steam driven Pullman car from Victoria Station to Dover and back. And I’m so glad I did. Those few hours on a glorious hand-crafted luxury carriage were truly an immersive experience. The rattling of the silverware and the ringing of the crystal as the coal fired locomotive wended its wobbly way through the garden of England was enough to make my bifocals mist up. Yes of course, much of Kent is a shithole now, but viewed from the splendour of our marquetry clad interior, England looked rather lovely. Hopeful, even.

Of course it was all a bit of play-acting. Naturally, I dressed for the part in three piece tweeds, pocket watch, homburg and umbrella but these personal props weren’t just accessories, they were personality adjusters. I found myself sitting more upright, annunciating more precisely and folding my linen napkin with new found balletic elegance. After all, the refined environment I’d properly shelled out for expected it of me. And so I obeyed.

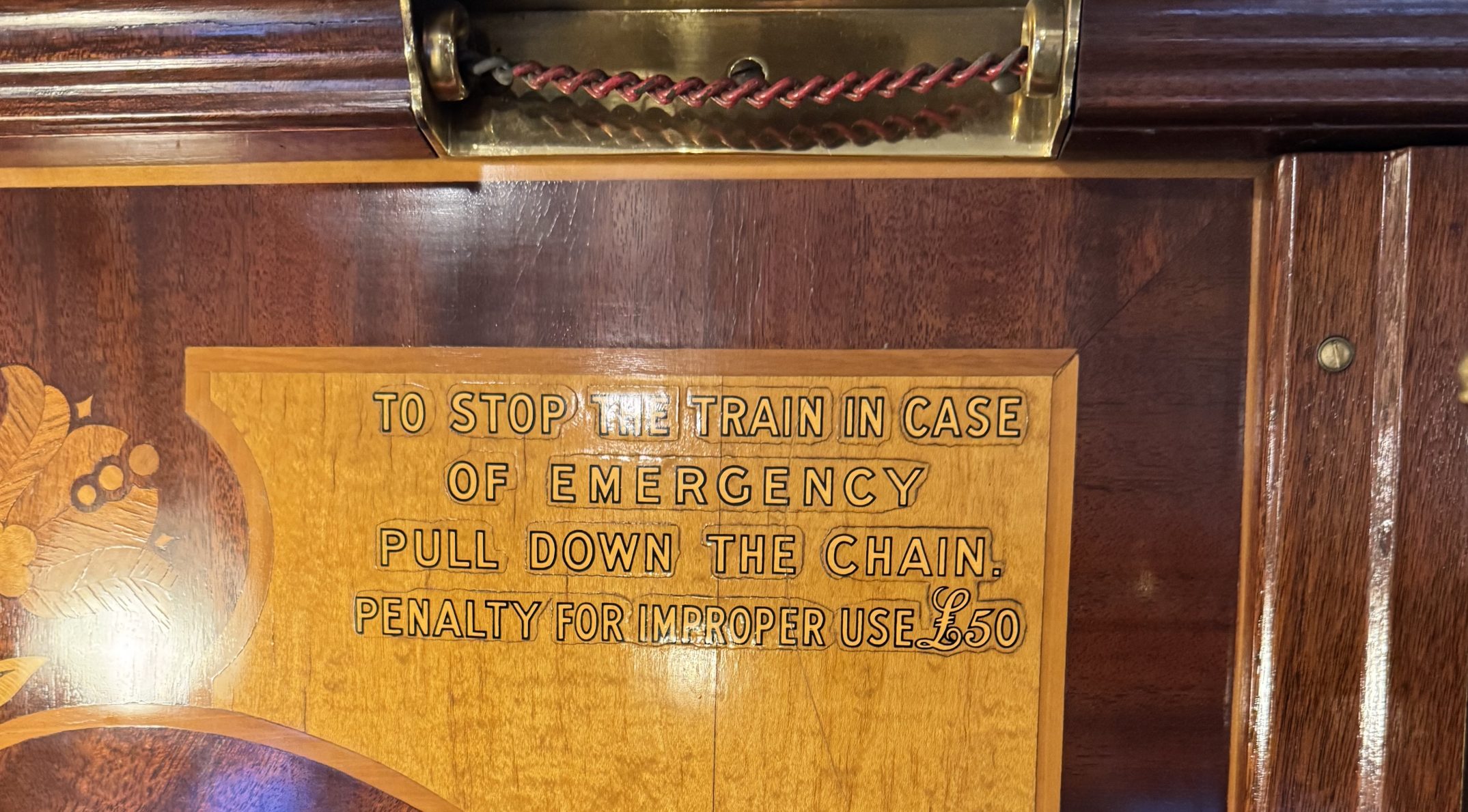

Contrast this with today’s first class train travel experience. The crystal glasses have been replaced with much safer disposable plastic beakers. Gone is the silverware (clearly it would all get stolen and melted down to make nose rings). The linens haven’t been seen since the invention of Formica and the exquisite hardwood interiors have obviously been replaced with much more practical graffiti resistant laminates. Perhaps the most striking difference is the arrival of the shouty warning signs and messages that constantly tell us off and warn us of all the things we shouldn’t do on every…available…bleedin’…surface. These signs are simply there to back up the endless robotic announcements about things that we might be doing wrong like leaving bags on seats, smoking in the toilets or not noticing terrorists, for example.

You see. Warning signs and safety messages don’t always have to be ugly and shouty.

This massive cultural shift is a direct result of a series of highly practical, sensible decisions to improve things for everyone over the course of a hundred years or so. I can only assume that a Victorian yobbo once lobbed a crystal glass from the window at some point. A heinous crime that we are all, quite rightly, still being punished for a century and a half later.

Look, I know that the past is a safe place, a more innocent place, a distant land that we see as cleansed of today’s nauseating politics but, seriously, it’s not just luxury we’ve lost here…it’s the way in which our environments judge us. My Pullman experience was a stark reminder that once upon a time spaces and places actually wanted us in them. They brought us the very best the planet had to offer in luxurious fabrics, food, fine wines and personal service, and in return they demanded our respect and courtesy. The result was the undisputed golden era of public transport.

I guess what I’m trying to say is that our environments shape us, shape our behaviour our attitudes and our responses. Allowing the lowest common denominator to take ultimate control over the last century or so has delivered us an ugly, distrusting and perpetually suspicious built environment that doesn’t really want us in it. And that is no way to design the future.

So, in answer to the endless request “If you see something that doesn’t look right..”

Well yes everything, pretty much.

Even the loos are dressed to impress

Howard Saunders is a writer, speaker and The Retail Futurist

howard@22and5.com

@retailfuturist